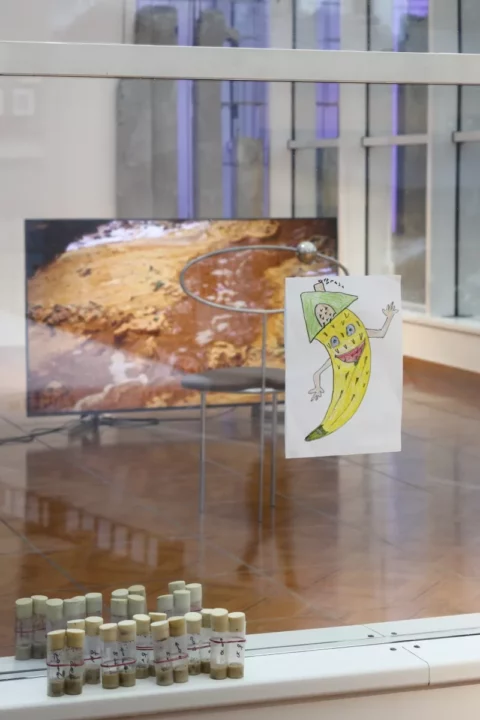

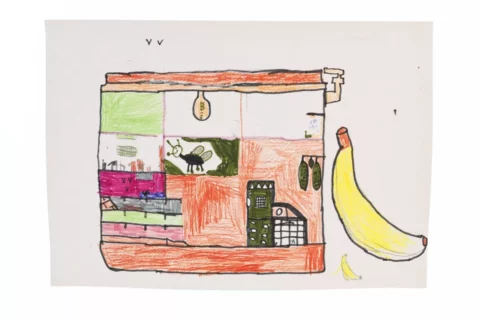

Participants: children, fruit flies, Mark Eckstrand, Adrian Ganea & Chlorys, Mindaugas Gapševičius, Helena Heinrihsone, Kamilė Krasauskaitė, and other significant and nonhuman others

A new wave of pandemics brings us another opportunity to reconcile with the agency and representation of nonhuman others. Something very common for this time of the year — a fruit fly — could be used as the metonymy for the non-human. Living nearby, together, and being visible, it could reveal how non-humans may be imagined, understood and treated artistically, practically, or scientifically.

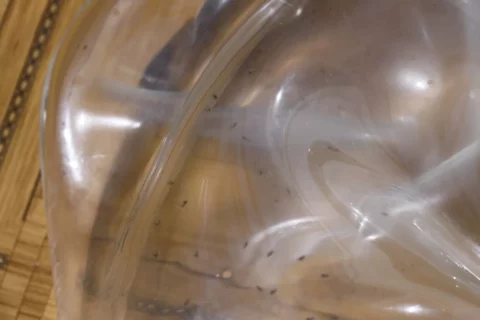

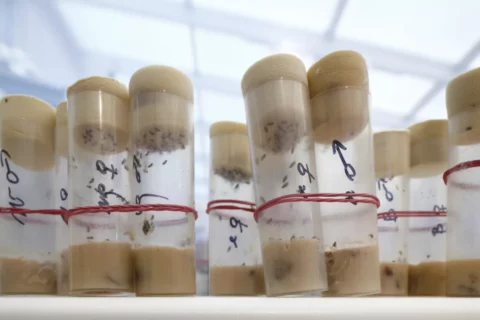

The exhibition title, which refers to the overwhelming intimate lives of fruit flies, is a found clickbait. This situation refers to the phenomenon that the fruit fly, “Drosophila melanogaster”, is commonly used as a human substitute in scientific experiments to understand human behaviour and its genome. The fruit fly is used as a model organism to study disciplines ranging from fundamental genetics to the development of tissues and organs. The Drosophila genome is 60% homologous to that of humans, less redundant, and about 75% of the genes responsible for human diseases have homologs in flies. Fruit flies are instrumental in the production of scientific imagination where they also serve as human projections or representations. Fruit flies are popular among the scientific community because they are expendable, easy to control, count, monitor, and have clearly expressed genders.

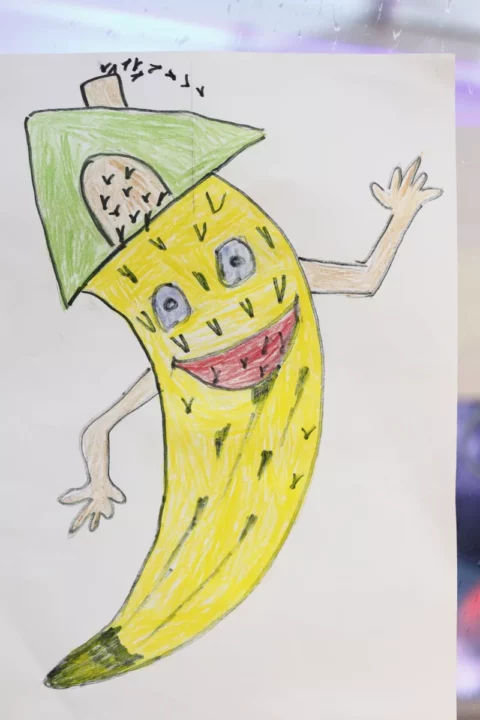

However, you might want to hear more about the clickbait title experiment. Scientists used a technique called optogenetics, which involves the use of light to control neurons. In this case, scientists knew which neuron controlled the release of sperm. By exposing the fruit fly to a red light, they were able to activate that neuron, causing them to ejaculate. The work implies that sexual pleasure — and in this case — an overwhelming one, is not limited to mammals. One more indicator that fruit flies enjoy sex is their reaction to alcohol — sexually deprived male flies prefer an alcohol drink over a non-alcoholic one, seemingly as an alternative reward. According to various articles that popularise science, scientists already know a fair amount about fruit fly intimacies. According to one such article, the male fruit fly’s penis has sharp hooks and spines that serve as Velcro, letting it keep hold of the female. The same article states that fruit-fly semen is a strange brew, containing chemicals that can stimulate the female to lay more eggs (thereby increasing the male’s reproductive success), store more of his sperm, dull her interest in other males that come along, and make her more aggressive toward other females. A fruit fly could find itself trapped in worse experiments. In one, they have their genitals lasered, or vivisected, or their circadian-clock genes removed, forcing fruit flies to drift from test tube to test tube not knowing what time of day it is.

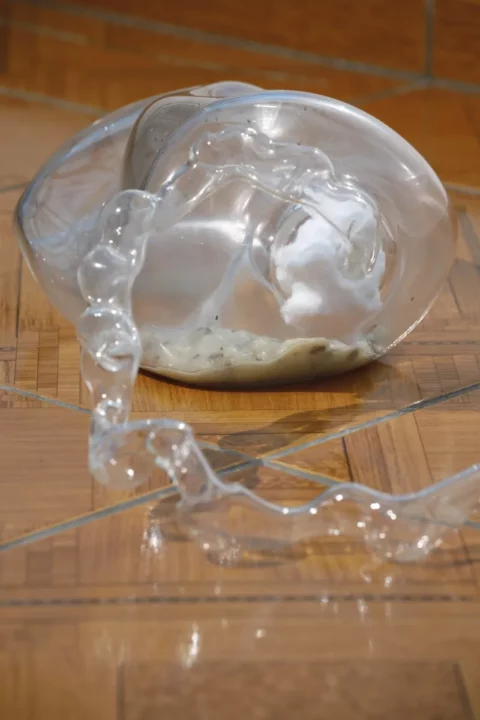

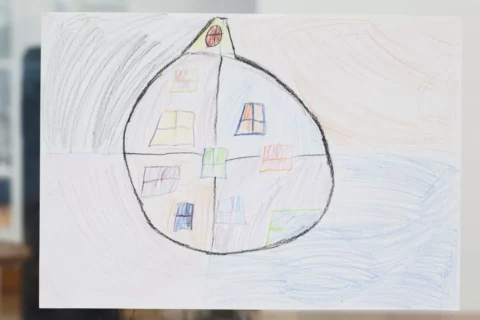

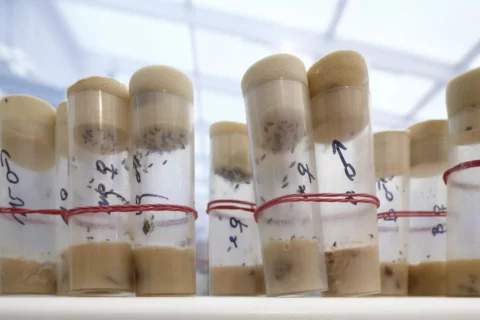

Apparently, for decades scientists have detailed the intricacies of ‘male’ fruit fly sexual behaviour and neurobiology. This isn’t the first time someone notices science’s tendency to prioritise male sexuality and males in general. There are studies demonstrating that scientists display a marked preference toward studying male genitalia, as opposed to female genitalia. This, some researchers say, has to do with how obvious the fruit fly males’ behaviours are — they’re easier to study and are more eye-catching; however, others suggest it has more to do with the lens through which scientists look at male and female behaviours. However, from one research to another, a pattern emerges. The brain’s reward system, whether fly or human, seems to be rather rudimentary, seemingly reinforcing one behaviour when another isn’t possible. This thought also allows us to interpret this exhibition as an experiment that would include not just non-humans but also its spectators, lured by its clickbait title, familiar names or a possible glass of yeast drink at the opening, among other things. Or forget the barfly reference and think how abstract forms and shapes, the smell of bread, vivid colours, lights, or the soundtrack might activate certain brain neurons and how aesthetics also may be interpreted as a certain alternative reward.

The open question is, what kind of a reward and a reward for what exactly?

Valentinas Klimašauskas

Thanks to: Eglė Tatjana Čėsnienė, Juris Dunovskis, Tuçe Erel, Antanas Gerlikas, Ieva Līcīte, Dace Vulfa

Partners: Dunov Glas, Institutio Media, VšĮ “Stiklo svajonės”, Jonika Depo Design

Supported by: The Nordic-Baltic Mobility Programme, VKKF, Sony, GaCo Sound Light Stage