The division of work has taken its share of twists and turns, both transmuted and transfixed us by our desire for activity and production, but also to earning us the sweet “fruits” of our labour. We hyper-competitive, hyper-individuals single-handedly applaud the success of others as we intensely engage in various forms of material and immaterial work, often at great cost to our contemplative lives, yet rewarding ourselves with seemingly tangible riches. Google continues to exploit low-wage workers digitising physical books for our online reading pleasure, while Amazon employees are monitored and measured for “performance” in dystopian conditions to fuel our insatiable appetite for having things sooner rather than later. In a bizarre vision of beta-version capitalism, luxury SUVs sit parked below Khrushchev era apartment blocks around Riga – the cars worth monetarily more than their owners’ home – within now decaying low-cost concrete complexes built by then Soviet soldier labour – in the heroic image of the “worker”. But socio-economic hierarchies of class and “keeping up appearances” matter in a newly independent country colonised and stripped of its cultural identity for so long.

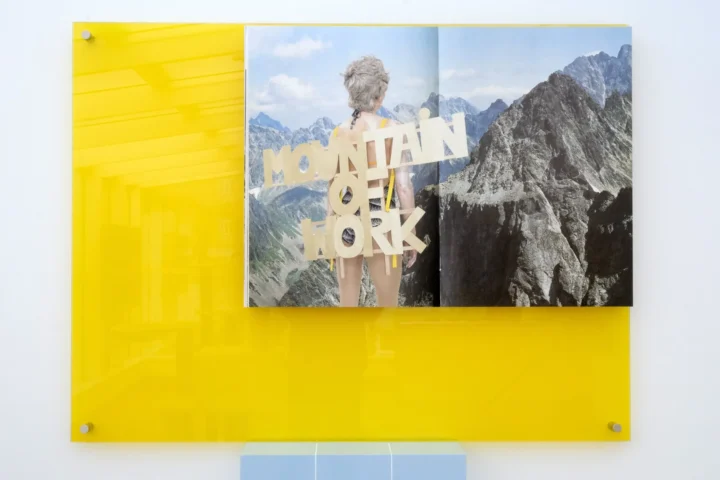

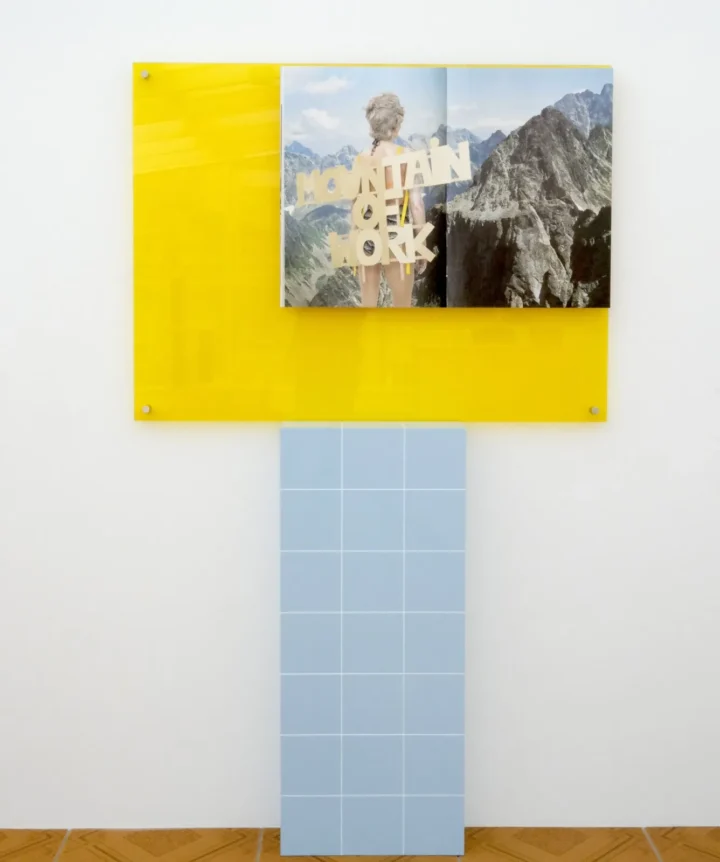

Work is life in old and new Latvia, despite newly embracing self-care routines, a “visible” work/life balance, and the accompanying absurdly cheap flights to exotic destinations a free-market affords EU members. Sigrid Viir often engages with labour precarity and the blurring lines between work, rest and play in the post-digital, an epoch where public and private realms are increasingly conflated. As her native Estonia embraced the digital economy more than the other Baltic states, Viir shows us the blurred lines where one ceases to be “at work” and one is ever-present online; producing and performing – even when on holiday. The Baltics are deemed the most “productive” of all the former Soviet regions, yet one has a nagging feeling that a victim mentality and pacified societal discourse is perpetuated by the seeming necessity of constant work. This is perhaps as much a symptom of work addiction as a form of trans-generational trauma and hangover of the Soviet-era, as it is also a sign of ongoing disparate economic conditions – in a region still paying an absurdly low minimum wage by western and middle European standards.

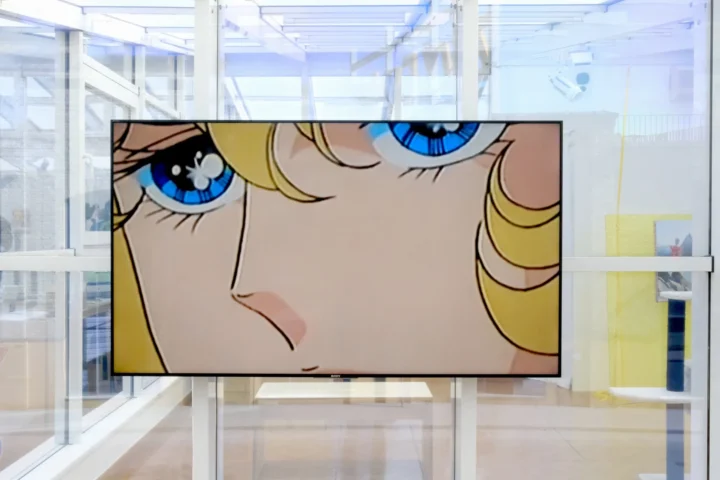

While sitting in a Riga taxi considering Fordism and class privilege (and sensing the irony), my driver casually unleashes a racist diatribe on me towards South Asians working as low-wage food delivery drivers, students who, desperate for a European education, emigrate to the borderlands of Europe and try to make ends meet, facing exploitation, discrimination and xenophobia. As Vika Kirchenbauer’s video work reminds us, envy is accompanied by the irreverent shame of anger, intersecting both the past and present social realities of work and class. In this case, choice is perceived from one side of a two-sided coin – the have and the have-not. Meanwhile, a historical “brain drain” slowly leaks away talented and ambitious young Latvians who seek to have higher wages, better education, social services, and, well, a better work/life balance. But are these indeed now inseparable? Henry Ford’s week-end never really meant much to “essential” workers, cultural sector or gig-economy labourers engaged in various precarious forms of labour that don’t fit an outdated binary of paid employment. Yet we still equally persist in the self-valorisation of perpetually being “busy”, of hating Mondays, but #TGIF because when the weekend hits – fun, entertainment and leisure-time awaits!

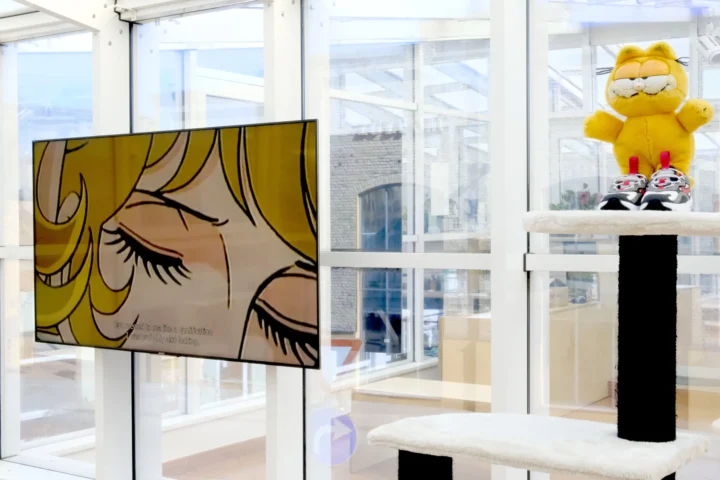

Of Mondays and irony, Australian artist David Attwood’s readymades playfully combine Garfield’s ironic attitude to work and leisure, simultaneously lambasting the working week as an apparently able participant in forms of capitalist labour – all the while embracing activewear and the lazy, sedentary lifestyle of a housecat. Sports leisurewear is a big deal in past and present Latvia. What are ubiquitous working class garments in the West were equal parts fetish objects and status symbols of class hierarchy in the Soviet Union, peaking around the glory period of the Moscow Olympics in 1980. In some places it would cost a month’s wage for a smuggled Adidas tracksuit or pair of bootleg Levi’s, while others obsessed over Botas sneakers from former Czecho-Slovakia as an obtainable alternative to Western consumer brands. The irony of the African American slave history of denim was almost certainly lost to a nation (and Bloc) looking to simply “stand out” in a system that glorified the collective over the individual.

With longer queues outside Nike & Adidas stores than at vaccination centres in Riga during the height of the pandemic, one senses that the desire for fast-fashion “relaxed sportswear” has not abated, all these decades later. The synthetic fabrics in sports leisurewear are those commonly produced by what we now knowingly refer to as “sweatshop” labour. Today, most of the textile factories of the Soviet imperialist experiment, much like other former factory industries here, stand still as vacant, decaying vessels of production across the Baltics and in emptying towns and settlements of the former Soviet Union. Not unlike the interiors of German painter Enrico Freitag, whose mother was a textile factory worker in the former GDR, the assembly-line labour stitching, weaving and sorting such trendy clothing, among a myriad of other objects of desire, is now quietly invisible – outsourced to the Far East – and hidden in the global supply chain. But hey, work hard, play hard.

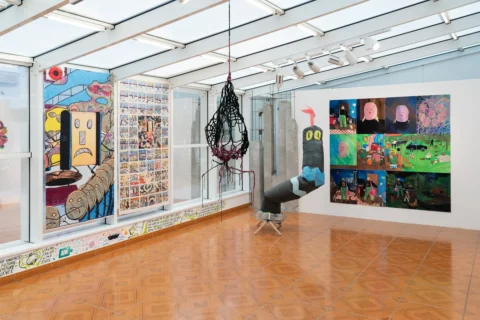

Far from any meaningful, in-depth critique of Marxism or Post-Fordist Capitalism for that matter, this exhibition scratches lightly at the complexities of labour and their representation, revealing a curious self-reflection on contemporary and historical depictions of work, our relationship with leisure, laziness, and art-making as a form of labour. These strange New Beasts of Burden are bound by their seemingly inherent need for modes of production, and, perhaps equally, a voracious desire to purchase, acquire and fulfil what they apparently lack.

David Ashley Kerr, March 2022.

Special thanks to SONY Latvia, Maija Rudovska, Elizabete Ozola, Liene Pavlovska, Mārtiņš Mežulis and all of the artists involved. LOW is structurally supported by the State Culture Capital Foundation, Latvia.